Influenza and Tuberculosis prevention poster

Courtesy of Gloria Stephens

Prompt Nova Scotian actions minimize the effects

As horrible as the ravages of influenza were in Nova Scotian communities, its effects were not as severe as in other parts of Canada or the United States. Although it took some weeks for the public health response to gear up, several factors helped to limit the pandemic’s spread and the number of Nova Scotian deaths. Quickly sending doctors to Boston to learn from the experience of Massachusetts and to make public health recommendations was perhaps the most important of these. Combined with the experiences of Nova Scotian nurses who went to Massachusetts at the outset and then returned home to help, and the fortuitous situation of having a medical doctor as the mayor of the largest city in the province, Nova Scotia had an advantage compared to other locales. Finally, many government officials, hospitals, doctors and nurses (including the VADs) had the recent experience of the 1917 Halifax Explosion behind them. All of these factors undoubtedly assisted in quickly making plans for quarantine hospitals and the logistics of other public health arrangements during the influenza epidemic.

Public Health Statistics

The official public health statistics published immediately after the pandemic noted 1,769 deaths from the flu, out of an estimated total Nova Scotian population of 514, 484. This meant that the official Nova Scotia rate of 3.4 deaths per 1,000 of population was considerably lower than many other provinces such as Québec (4.5), Saskatchewan (5.9) or Alberta (7.6). It was significantly lower than the rate in Massachusetts (6.2) and for the United States overall (6.1). Even if this rate is recalculated using the higher figure of 2,265 deaths based on the new data uncovered in this research project, it remains low, at approximately 4.4 deaths per 1,000 of population.

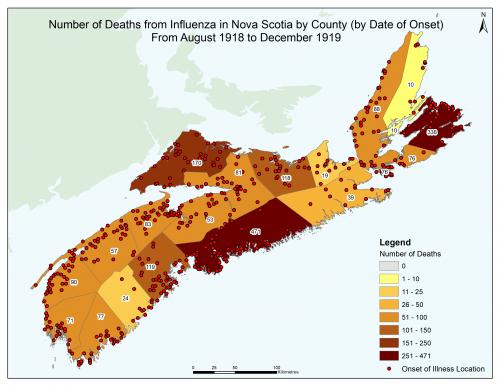

Spanish Flu Concentration Areas between August 1918 and December 1919

This “heat map” shows the areas of Nova Scotia which were hardest hit by the influenza pandemic. Each dot represents a community that experienced deaths from the flu, while the dark red colours represent the worst-affected regions of the province, in terms of total deaths.

Map by Nova Scotia Museum/Matt Meuse-Dallien and NSCC Centre of Geographic Sciences/Emily Cantwell.

Effects on small communities

Some smaller communities in Nova Scotia were devastated. With healthy, younger people in the prime of their working life being harder hit than older individuals or children, if a small community lost its working population the effects could be dramatic and long-lasting. One or two smaller rural communities may have disappeared due to deaths from the pandemic and survivors moving elsewhere. When influenza deaths are combined with the effects of the dead and injured Nova Scotian soldiers from the First World War, and with the casualties of the 1917 Halifax Explosion, the end of the war in November 1918 must have been bittersweet for many Nova Scotians in these dark days.

Dalhousie Public Health and Outpatient Clinic under construction (at left), February 3, 1923. The new Tuberculosis Hospital is in the background.

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 31, Folder 18 Item 3

Public Health legacies

That said, there were some positive outcomes from the pandemic. It highlighted an overreliance on physician care versus nursing care in public health, and such deficiencies were overcome by expanding public health care, particularly for the urban poor and rural areas. Canada established the federal Department of Health in March 1919, and Nova Scotia reorganized its Department of Health the same year, in response to lessons learned dealing with influenza.

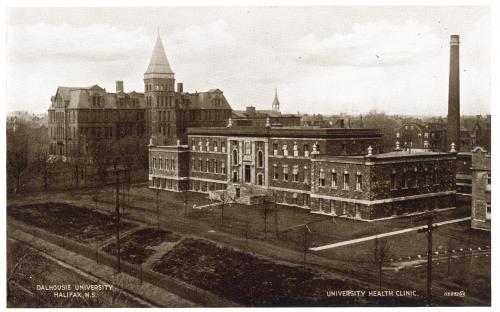

Postcard of the completed Dalhousie University Public Health Clinic. The cornerstone of the building noted that “It was erected to facilitate the training of medical students in methods of caring for the public health and to assist in alleviating sickness and suffering in the city of Halifax.”

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 61, Folder 165

New focus on prevention of disease

Prevention of disease was now given a higher priority in medicine than it had had prior to 1918. For example, Dalhousie University obtained a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to establish a Public Health Clinic which opened in 1924. The new Infectious Disease Hospital and Tuberculosis Hospital at Dalhousie were constructed in the same period. The goodwill generated by the Nova Scotian nurses who volunteered to assist in Massachusetts, and their sacrifices, no doubt contributed to the development of the close relationship between Boston and Halifax which continues to this day.

The new post-pandemic Infectious Disease Hospital in Halifax.

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 31, Folder 15, Item 8

The new post-pandemic Tuberculosis Hospital in Halifax.

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 31, Folder 15, Item 10

The importance of vaccinations and immunization

The public health legacies of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 to 1920 live on today. Many of the public health measures developed at that time have been built upon over many years to battle similar viral outbreaks today, including the H1N1 and other strains of influenza such as “bird flu”, as well as other viruses such as SARS or Ebola. The importance of developing vaccinations and immunizing populations against all forms of viruses, including formerly-thought-to-be-eradicated common childhood illnesses such as tuberculosis, measles and polio, remains paramount in preventing future pandemics and childhood deaths. Medical research into the different strains of virus found in “Spanish” influenza continues today. New research findings from such work assist in the development of vaccines to protect the public from future influenza pandemics.

A waiting room in the new Public Health Clinic at Dalhousie University.

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 31, Folder 19, Item 3

A vaccination clinic at the Dalhousie Outpatient and Public Health Clinic.

Courtesy of the Dalhousie University Photograph Collection, Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia, PC1, Box 30, Folder 31