How did the War of 1812 affect trade and privateering in Nova Scotia?

Credit: “War of 1812 Liverpool Packet” by Thomas Hayhurst, Queens County Museum, Liverpool, NS.

When the War of 1812 started, the ports of Nova Scotia were already doing a busy trade due to British demand for supplies for their army fighting Napoleon in Europe. Wanting to continue this prosperous trade, Nova Scotia’s Lieutenant Governor, Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, successfully lobbied the British government to allow Halifax and other towns to trade specific articles with American ports, despite being at war. By the third year of the war, Halifax’s port revenues had tripled.

Many made their fortune with trade, fees and military contracts. Among these were Nova Scotia’s now famous merchants, Enos Collins and the Cunards, as well as Richard John Uniacke, the Province’s attorney-general. Uniacke was paid handsome legal fees for processing each of the over 500 Royal Navy captures and 250 privateer captures. His wartime earnings paid for Uniacke House, his country estate home built at the end of the war, which is now a Nova Scotia Museum site.

The prosperity wasn’t limited to those dealing directly with the ships. Farmers, fishers, woodsman, artisans, inn keepers, and even brothels all saw an increase in the demand for their wares. This improved the lives of many, but also created large areas of unsavory activity in Halifax.

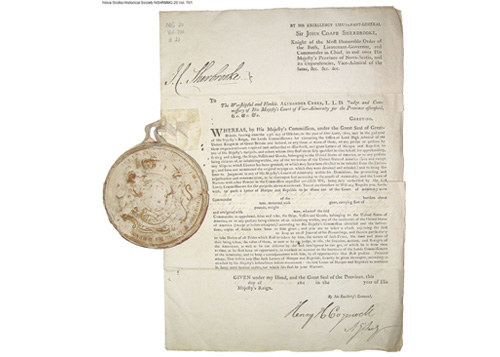

Credit: “Letter of Marque, Liverpool Packet and Seal”, Nova Scotia Historical Society NSARM MG 20 Vol. 701 #21

Privateering could be another hugely profitable venture, although it was also very risky. Licensed by a special court, privateers captured American merchant vessels and their cargo as prizes, while also providing useful intelligence to the Royal Navy. The most lucrative privateer to sail in Nova Scotian waters was the Liverpool Packet, whose captain used its profits to purchase Perkins House, now a Nova Scotia Museum site.

Privateering continued throughout the war, and even afterwards, as news of the end of the war did not arrive in the colony until more than two months after the Treaty of Ghent was signed in December 1814. Soon, the new-found prosperity that so many had enjoyed disappeared, ushering in the onset of a post-war economic depression.

More:

- The Nova Scotia Archives offers “Spoils of War: Privateering in Nova Scotia”, a collection of archival resources related to privateering in the province.

- Perkins House Museum offers a short overview about privateering along Nova Scotia’s South Shore in the resource “What was Privateering?”.

- The Liverpool Privateering Days commissioned three statues as a commemorative monument to local 1812 persons.

- Uniacke Estate Museum Park provides a brief biography of Richard John Uniacke.

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography’s entry for Sir John Coape Sherbrooke.

- As part of a six-part series about significant people during the War of 1812, Canada 1812: Forged in Fire, in partnership with Parks Canada, provides a biography of Enos Collins.

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography’s entry for Samuel Cunard.