What do we remember when we remember William Hall?

Heritage Day, 2024

Heritage Day 2024 celebrated the life and legacy of Mr. William Hall, V.C., the African-descended Nova Scotian farmer and naval hero. What do we celebrate when we celebrate William Hall, his life, and his achievements? For more than a hundred years, Black Nova Scotians have celebrated Hall as a good neighbour and dutiful family member, as a courageous Black man who overcame entrenched race-based prejudices to live as freely and generously as he could.

For nearly as long, veterans and military personnel have remembered him as a superb seaman and naval gunner who embodied the highest ideals of the codes by which they live. Nova Scotians outside the Black community have likewise celebrated Mr. Hall, for reasons that shift emphasis in tandem with the changing character of the province itself during the past 150 years.

It’s timely to reflect on Mr. Hall and his legacy, on how he has been remembered in the past, and how his achievement and inspiration might continue to serve Nova Scotians, present and future. Commemoration of Mr. Hall’s life is a long arc, an arc that includes many, but which starts and ends with his family and his community—his first and most constant rememberers.

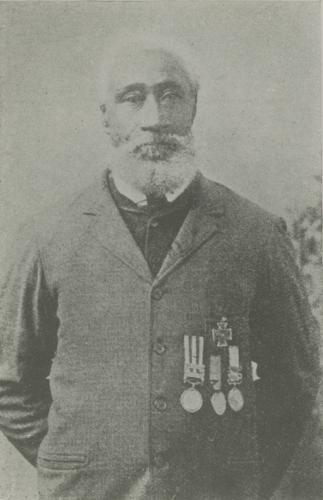

1. Portrait of Mr. William Hall wearing his Victoria Cross and medals earned during service in Crimea and in India.

Credit: Nova Scotia Museum, Marine History Collection, MP400.60.1

2. William Hall stands high in the bow of HMS Shannon’s ship’s boat as it rescues a man overboard at sea in 1857, the same year he earned his Victoria Cross. It was the third rescue this crew had made on the voyage.

Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Navy and Empire

William Hall served in Britain’s Royal Navy for nearly a quarter-century. Much of his career in the navy was commemorated more-or-less as it occurred. The campaigns in which he participated—in Crimea, in India, in China—were widely reported on, represented, and celebrated by growing 19th-century popular media. Britons of the time—firmly convinced of their civilizational superiority—saw colonizing efforts overseas as essentially philanthropic (a conviction belied by the coercive and exploitative character of much contemporary British imperial activity overseas).

In this context, Mr. Hall’s lifesaving courage and his coolness under fire while in the face of Indian resistance to British power were seen to be of a piece: each demonstrated extraordinary valour in the service of British values and civilization as they expanded worldwide. As the complicated and brutal events of 1857 were distilled in British (and Anglo-Canadian) popular culture to an appalling essence of racialized and gendered violence, William Hall and his fellows at the Relief of Lucknow became widely lauded heroes of empire. And so, the formal, dignified service at which Mr. Hall received his Victoria Cross (apparently preferring a shipboard service to receiving it from the Queen herself): fellow seamen manned the ship’s yards, officers in full-dress stood by, the ship’s band played “God Save the Queen” as the medal was pinned on his chest.

3. The lighthouse at Horton Bluff, Nova Scotia, near William Hall’s childhood home. In the background is North Mountain/Cape Blomidon, the Minas Passage, and the maritime world beyond.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

Home Place

In 1872, after a lifetime spent at sea, William Hall retired to live and farm on land near his childhood home at Horton Bluff. There his labour and navy pension helped support his sisters, with whom he lived. Mr. Hall was known and respected locally, with strong links to family and faith communities. Decades passed in his “home place”. His service records grew old and tattered, so he burned them. His medals he kept stored in a box. As years passed, old shipmates, fellow veterans, the historically curious and the patriotic sought him out. Late in Mr Hall’s life some came hoping to draft his valour in service of a new nation: Canada.

4. William Hall at home, around 1900. Mr. Hall’s Victoria Cross ribbon has been replaced here by a watch-chain: a sticky-fingered visitor walked off with the original.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

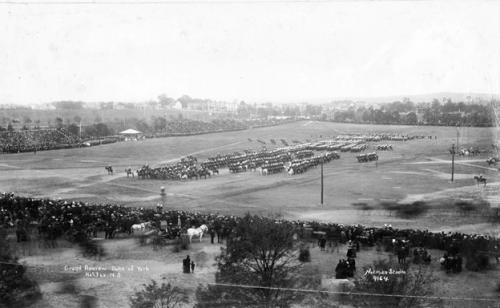

5. In 1901 the Duke of York and Cornwall, future King George V, visited Halifax. William Hall was invited to parade with fellow veterans and to a reception where the Duke spoke with Mr. Hall.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

Canadian Hero

The turn of the 20th century marked a crucial pivot for the Canadian nation: as Britain withdrew its military from North America (the last British forces left Halifax in 1905/1906), Canada began to assert itself overseas militarily. Many Canadians—including Nova Scotians—fought and died in the Second Boer War (1899-1902); survivors sought to create distinctly Canadian traditions within which to understand their experiences. William Hall became—and remains—an iconic figure in this national military heritage.

William Hall’s elevation to heroic status in Canada’s military-historic pantheon stems from an apparently unlikely source: longtime Halifax resident and former Confederate States Navy officer John Taylor Wood. Wood served with Mr. Hall in the U.S. Navy before the Civil War. Wood’s son served in the Canadian and British armies and was killed in the Boer War. In the aftermath Wood—an unreconstructed former senior agent of the white-supremacist Confederate States government—sought out his Black shipmate. Their conversation informed the most detailed accounts of Mr. Hall’s career published to that time. Reference to Mr. Hall’s race is notably lacking in Wood’s account.

William Hall’s 1901 Halifax encounter with the Duke of York and Cornwall, the future King George V, was seen by people at the time (and since) as affirmation at the highest level of Canadians’ loyalty and courage in service of an empire of which they were an increasingly important and aggressive part. This first wave of public remembering held up Mr. Hall’s career as a fundamental building-block of a growing nation’s military tradition.

6. Funeral procession for William Hall, 1904.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

William Hall’s 1904 funeral was well attended by family members, friends and neighbours, and military veterans. John Taylor Wood, British Army officers stationed in Halifax, and members of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society sought to retain Mr. Hall’s medals in the province as a testament to the province’s martial valour, without success.

The public recognition spurred by Canada’s participation in the Boer War did not last: Nova Scotians were soon consumed by the vast waste of the First World War, the 1918/1919 global pandemic, and by economic depression through the 1920s and 1930s. All this time, William Hall’s legacy was safeguarded almost exclusively by the two communities with which he was most closely identified: the African-Nova Scotia community, and the Canadian military community.

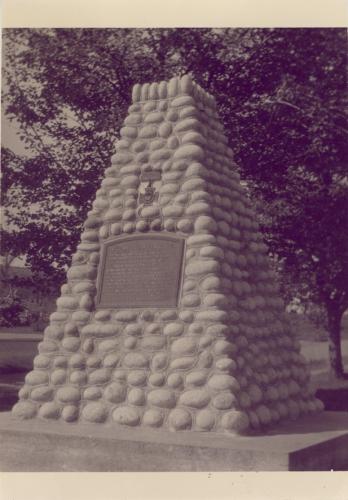

7. Memorial cairn at the gravesite of William Hall, V.C., Hantsport, Nova Scotia.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

Keeping the Flame

In 1947 Black and military communities combined to move Mr. Hall’s remains from their unmarked resting-place and to reinter them prominently in front of Hantsport Baptist Church. A cairn memorializing his heroism marks the site. A letter from the Halifax Coloured Citizens Improvement League read at its dedication invokes Hall’s significance to the Black community and to the nation, while—perhaps—pointing beyond the imperial emphases of earlier memorials. The League expressed “...great joy at this lasting memorial to one of our race who devoted his life to the Empire which symbolizes peace, good will and tolerance among all peoples and all climes.

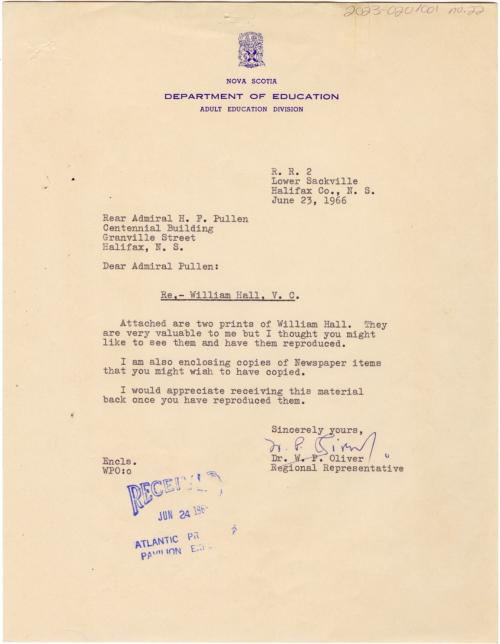

8. William Hall’s legacy resides fundamentally with his descendants and with Black community members, including the late Dr. William Pearly Oliver, civil-rights leader and longtime pastor of New Horizons (formerly Cornwallis Street) Baptist Church.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

Prominent members of the African-Nova Scotian community, including the Reverend William Pearly Oliver, kept the flame of remembrance burning during long decades of neglect through the mid-20th century. As Canada approached its 1967 centennial year, people outside the Black community again turned their attention to Mr. Hall, now as an icon of Nova Scotian and Canadian identity.

Centennial Icon

Rear-Admiral Hugh Pullen, overseeing the Atlantic Provinces Pavilion at the Expo 67 World’s Fair, energetically (and successfully) sought to repatriate Mr. Hall’s medals which had been sold overseas during the 1920s. Pullen worked in coordination with Dr. Oliver, regularly stressing the medals’ unique significance to Nova Scotians of African descent in correspondence.

The Nova Scotia Government’s 1966 acquisition of William Hall’s medals was a remarkable early instance of effective collaboration between local Black communities, the Canadian military, and the provincial government. The medals were displayed at Expo 67 in Montreal and the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa; they were present at the Centennial Memorial service in Hantsport the same year. The medals formally entered the custodial care of the Nova Scotia Museum in 1975.

9. In the mid-1960s, Rear-Admiral Hugh Pullen of the Royal Canadian Navy undertook a successful search for William Hall’s service medals on behalf of the Province of Nova Scotia.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

10. William Hall’s Victoria Cross.

Credit: NSM 75.100.1

11. African Nova Scotian communities and Canadian Forces personnel and veterans have remained driving forces behind commemoration of William Hall’s legacy.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

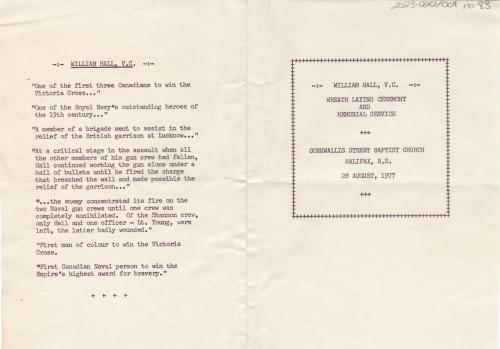

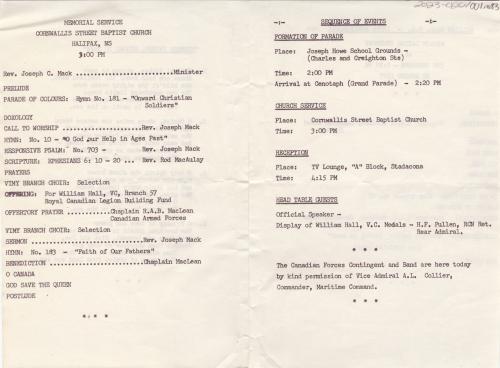

Since 1975, Mr. Hall’s medals have travelled to memorial events highlighting his importance to African-descended and military communities. A 1977 memorial service jointly convened by Halifax’s Black community and the Canadian navy captured the character of joint-remembering perfectly: following a service at New Horizons (then Cornwallis Street) Baptist Church, participants marched through the historic Ward 5 Black neighborhood to lay wreaths at the Cenotaph in Grand Parade, the civic heart of Halifax. Mr. Hall’s medals have since attended naming and launch ceremonies for the Royal Canadian Navy and have formed the centrepiece of exhibits at the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia and the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

12. HMCS William Hall under construction at Irving Shipbuilding, Halifax.

Credit: commons.wikimedia.org

Legacies, Today

Continuing its long legacy of honouring Mr. Hall’s service, in April 2023 the Royal Canadian Navy formally named its fourth Arctic Offshore and Patrol Ship HMCS William Hall, honouring his memory and perpetuating his legacy of valour in today’s Canadian Forces. In keeping with established practice, the new ship will incorporate elements of its namesake’s African-Nova Scotian culture into its design.

13. William Hall is prominent among those honoured at the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, in Cherry Brook.

Credit: Communications Nova Scotia

William Hall’s legacy is cherished and maintained today by the Black Cultural Society of Nova Scotia, representing African-Nova Scotian communities provincewide. The organization’s cultural centre in Cherry Brook grew from a 1972 idea by William Pearly Oliver for an educational facility rooted in the rich legacies of Nova Scotian Black experience. Dr. Oliver is a central figure in transmitting Mr. Hall’s legacy into the late-20th century.

Remembering, Now

The ways in which Mr. Hall and his legacy have been remembered have shifted over time following broad cultural changes in Canada and the world. When his legacy first became known outside his home community at the beginning of the 20th century, it was in the context of a British-Canadian imperial outlook that was not yet prepared to confront its own race-based assumptions and prejudices. In present-day multi-ethnic, multi-national Canada, it is no longer necessary or appropriate to interpret William Hall’s achievements primarily in the context of the imperial wars in which his courage and character were so brilliantly employed.

Heritage Day 2024 offers an opportunity for Nova Scotians to further appreciate and broaden William Hall’s legacy, to discover and understand anew the breadth of lives and of communities that have been denied their rightful place in the life of our province. In important ways, Mr. Hall’s heroism stems from the facts that he, a Black man born in settler Nova Scotia to parents who had recently freed themselves from enslavement, took the opportunities offered to him, overcame the racial prejudice he faced, and became the absolute best in his profession—the profession of naval arms. It is a history and a legacy that serves as an enduring inspiration to all Nova Scotians, whatever their origin or outlook.

Roger Marsters

Curator of History

Nova Scotia Museum