Extracting a Fossil for Exhibit

Delicate fossils found in museum are cleaned, repaired, and mounted in archival supports when the fossils are put on display or used for research. This #FossilFriday we share an update on the museum conservation of the Gyracanthus magnificus specimen. Above is our Geology Intern, Robbie, using a wooden mallet, chisel, and diamond whetstone to chip away the very old plaster that the fossil fish spine was embedded within.

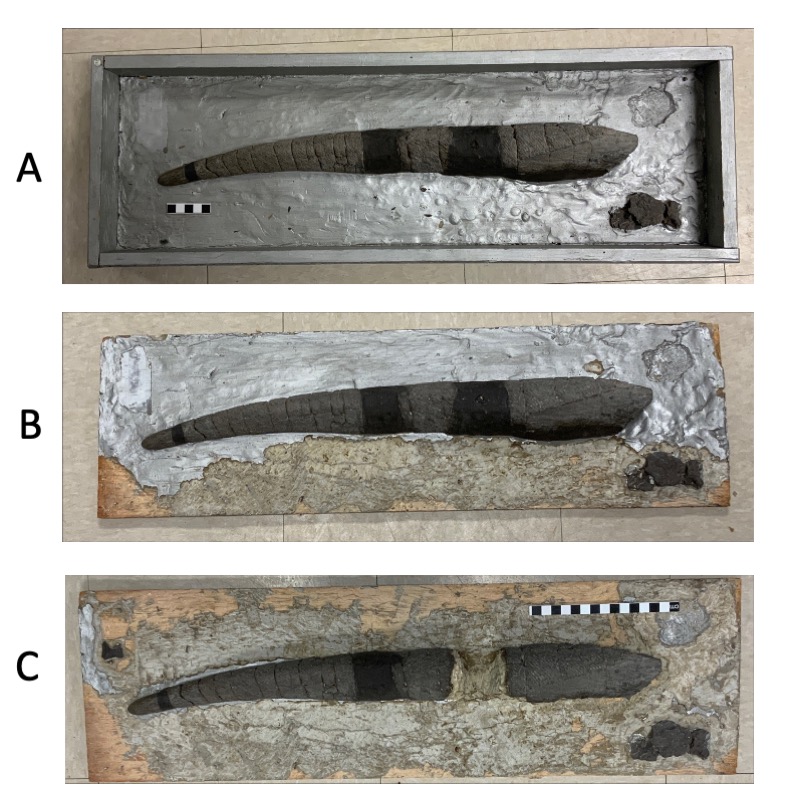

Unfortunately, the fin spine was plastered into this silver wooden box sixty or more years ago for display purposes (Photo A). As you can see, it would be undesirable on exhibit and does not allow for proper research of the specimen. The strategy for removing the spine was to carefully chip away the plaster surrounding the spine (Photo B and C). Then when enough plaster was chipped away, we started to dig out the plaster connecting the segments (Photo C).

With some plaster removed, we had the proper leverage to remove the first segment from its plaster prison with minimal damage (Photo D). The same tactic was used for the second segment, which only took around a week after the first segment was taken out (Photo E). A similar time went by to remove the final section; the Curator handled that due to its fragility.

The final step for the conservation of Gyracanthus magnificus was to remove the remnants of plaster that couldn’t be done with the chisel, which was finished recently (Photo F).

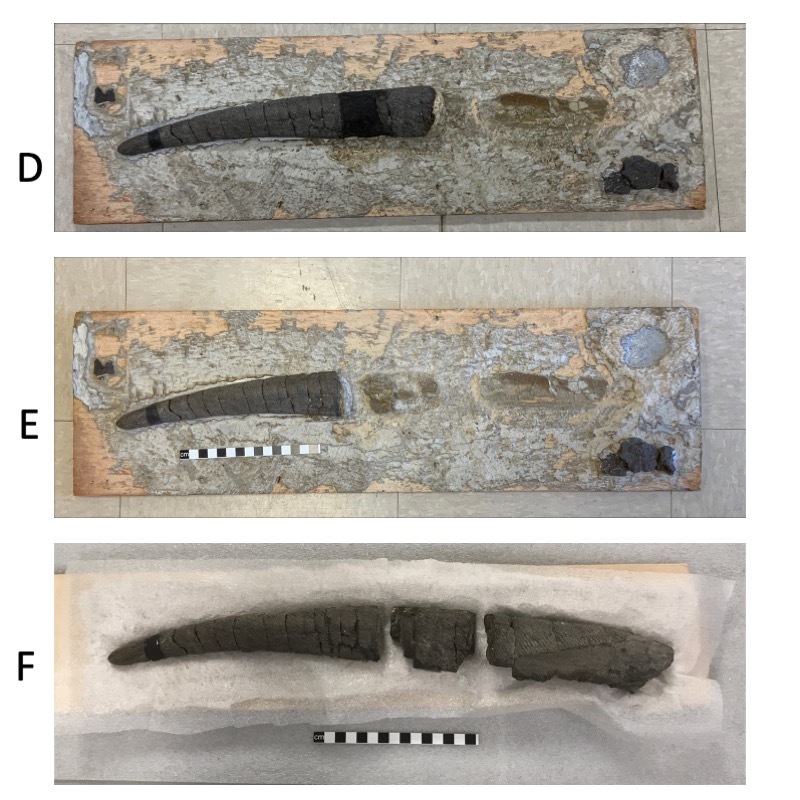

Above, the first picture is the published illustration of the fossil in Dawson’s second edition of Acadian Geology (1868). When looking at the spine in the box, it is clearly a very accurate drawing. However, now that it’s been removed from the plaster, we’ve been able to rearrange the pieces more accurately to show the natural curvature of the spine. This makes it 3 cm shorter than the original measurement of 55 cm.

All in all, it took an estimated 50 hours to excavate it from the plaster and then another 20 hours to remove the remainder under a microscope. This work was over a span of four months.

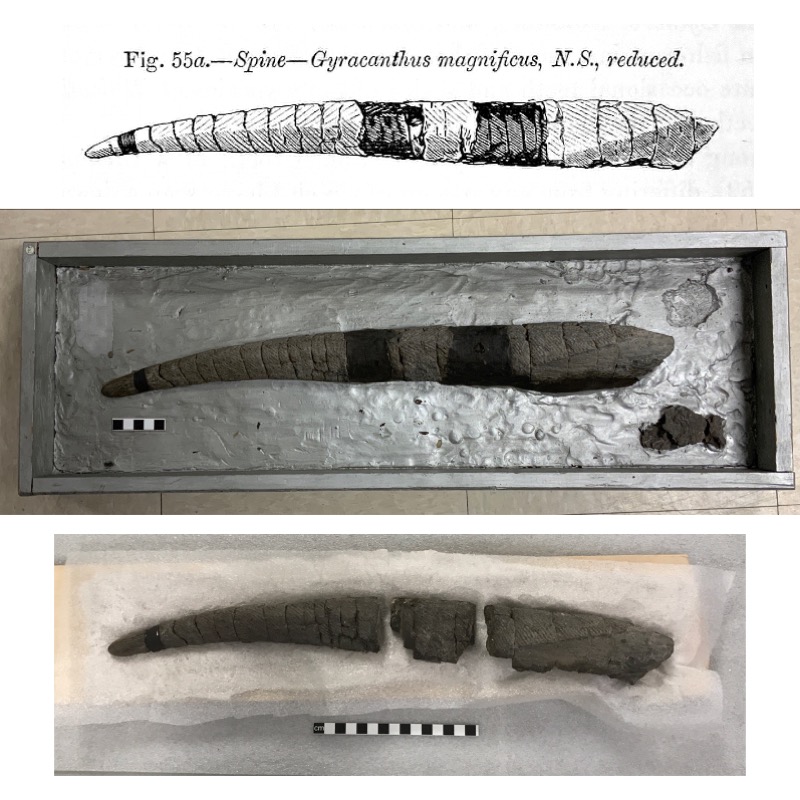

With the specimen now free from the plaster and available for additional research, we have also begun to carefully examine the Gyracanthus magnificus fossil under the microscope. The image above (A) shows the boundary between the finely ornamented external surface and the fine lines of an articular surface. The image below (B) shows small invertebrate shells that filled the hollow core of the fish fin spine when it was buried 325 million years ago. These may be helpful in providing more information about which specific limestone the fossil was found in 160 years ago.

Blog Post By: Robbie Hussey and Tim Fedak, Nova Scotia Museum