The African School sampler

Lisa Bower, Assistant Curator/Registrar, Cultural History Collection, Nova Scotia Museum

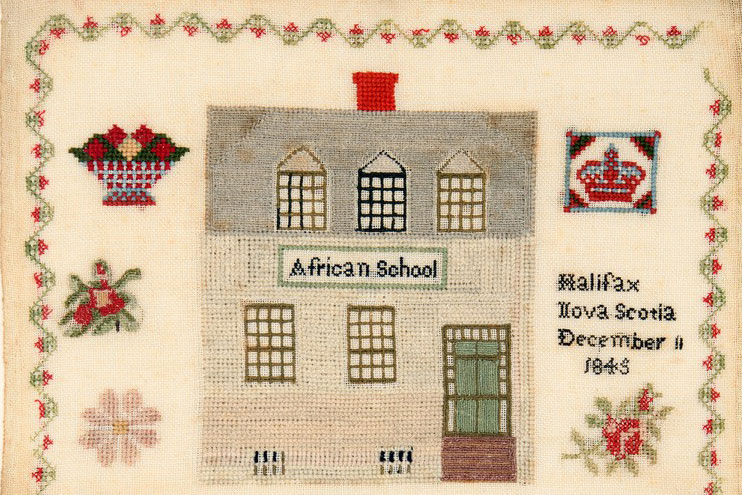

In my role working with the Cultural History collection, I have the privilege to care for many inspiring objects, including one of our recent acquisitions. This embroidered sampler is a rare example of this schoolgirl art form to have an attribution to the nineteenth century African Nova Scotian population through the African School (1836 – c.1858), Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Samplers are needlework pictures featuring hand embroidered motifs including the alphabet, numbers, verses, buildings or houses and scenes of biblical or secular subjects. The tradition of sampler making was brought to the colonies by settlers from Great Britain and Europe and is most commonly associated with the instruction of white girls, as part of their education.

The Nova Scotia Museum has over 80 samplers in its collection, but to date, none of them have been attributed to African Nova Scotian makers and at this date, I am not aware of any in other museum collections throughout the province.

Samplers from the Cultural History Collection

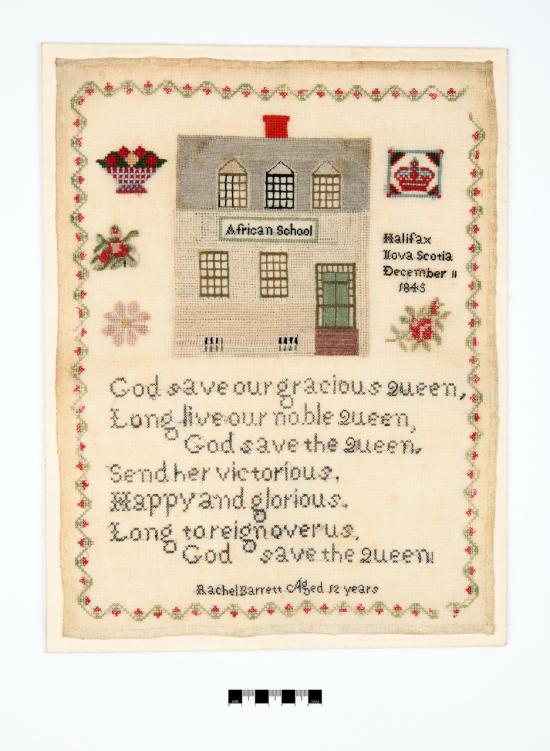

Rachel Barrett Aged 12 years

Cultural History Collection, Nova Scotia Museum, 2018.14.1.

Cultural History Collection, Nova Scotia Museum, 2018.14.1.

The sampler bears the maker's name: “Rachel Barrett”; her age: “12 years”; the name of the school: “The African School”; a date: “December 11, 1845”; and the location: “Halifax, Nova Scotia”. Although research is still in progress, the last name of Barrett appears on Halifax arrival lists for the Black Refugees and on local censuses. In Victorian-era Nova Scotia, the education of children was primarily segregated and only children of African descent, as well as their parents, attended the African School in Halifax.

According to Amy Finkel, of M. Finkel & Daughter, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania:

“The Halifax sampler is unusual in that it is the only known sampler made at a school for Blacks that is, in many ways, a classic sampler in composition, featuring a prominent house, various motifs and a verse. We are fortunate to have handled several samplers made at school for Blacks in the United States. This sampler by Rachel Barrett may be the only known Canadian example made at a school for African students. Its rarity and significance cannot be overstated.” Ms.Finkel was aware of our interest in the sampler, and, recognizing the significance of the sampler to the people of Nova Scotia, made us aware of its availability.

Rachel's sampler is embroidered using wool and silk threads and is on a background of linen fabric. It is interesting to note that the colours of wool used for the upper windows are varied...does this indicate a limited availability of supplies and that the maker was running out of a commonly used colour of thread? All of the stitching has been worked in cross-stitch, some over four threads and some over only two, the latter being more time consuming to execute, but resulting in greater detail. The depiction of the school house is large and central and it seems clear that care was taken with respect to specific architectural details. From the gap in stitching surrounding the windows (indicating the frame), to the roof (with what look to be dormers at either end), to the door with its surrounding glass panes, and finally to the windows at street level, all have been carefully delineated. Could this indicate an original design, rather than a commercially available pattern which was the norm?

Almost equal in prominence to that of the building are the verses of the British National Anthem, “God Save the Queen”. Records show that as early as 1836, the anthem had been sung during a public examination at the school, in honour of Emancipation, and that in 1837, wool was being purchased for needlework instruction. As the school relied almost entirely on funding from the provincial treasury and the favour of the London-based Anglican organizations that helped to establish it, it would have been important that the children were taught the anthem.

Girls were instructed in “needlework”, which included sewing, knitting, and the carding and spinning of wool as well as the weaving of woolen cloth, and “other work”. Sewing was considered an essential skill for girls to learn and the records indicate it would be useful as a means for self-support. Education for African Nova Scotians was preoccupied with religious and moral instruction and depended to a large extent upon the skill and attitudes of the instructors. No mention of sampler making has yet been discovered in archival sources related to the school, however, the existence of the sampler would seem to indicate that in addition to basic sewing skills, the tradition of sampler making was also being taught. It is possible that this tradition was considered beyond the normal scope of instruction for African Nova Scotian students at that time.

Boys also attended the school, but were instructed separately by a schoolmaster, the husband of the schoolmistress. Both sexes were instructed in reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and grammar.

The African School

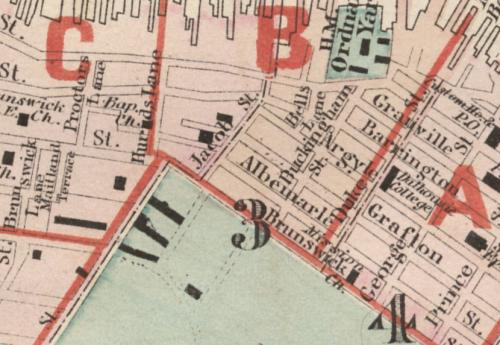

The African School was located on Albemarle Street, not far from the site of the present day Scotiabank Centre, but by the 1850s, when the school had begun its decline, the neighborhood had become one of the most crowded in the city. The poorest of the city's African population resided in this area and Researchers have established that it developed into slum-like conditions. Taking this into consideration, it seems all the more remarkable that Rachel's work has survived to present day.

It has only been in the last couple of decades that samplers made by African Americans began to be identified, researched and written about. Today, museums such as Winterthur, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the New York Historical Society and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, all possess examples within their collections. Although research is still in progress, we are not aware of any others to have been identified within Canadian museum collections.

Samplers made by African girls (both liberated slaves and colony-born) that attended religious based mission schools in Sierra Leone, have also been documented and researched. Dr. Silke Strickrodt of the University of Birmingham (UK) has researched and written about this group of samplers.

As the African School sampler is signed by its maker, it serves as a rare “testament” to Rachel's existence, but unlike a census document or arrival list, it is a product of her own making. It adds to our understanding of female instruction and how materials were used at the African School and confirms that this traditional schoolgirl art form was being produced by African Nova Scotians in the mid 19th century.

Research is ongoing, so stay tuned as more is discovered about the story behind the sampler and its maker!

Related Collections

Explore other collections with samplers: