Honeyman's Silurian Paradise

Guest Article By Alexandra Bonham.

Before becoming the first curator of the Nova Scotia Museum, David Honeyman found himself enamored with the rocks of Arisaig, Nova Scotia. During the 1850’s and 60’s he and his contemporaries – including William Dawson (i.e. author of Acadian Geology) – examined the coastal section in great detail. They recognized the scientific value in the marine fossils found continuously along the outcropping coastline. They were able to correctly conclude that the rocks at Arisaig are Upper Silurian in age. Today, the area is well studied and is regarded as Nova Scotia’s best locale for an accessible and complete Silurian stratigraphic record.

Nova Scotia’s Silurian

The Silurian Period began 443 million years ago and persisted for 25 million years. It is a period defined by the very first land plants, rebounding marine life, and a generally pleasant climate. During the Silurian we find present day Nova Scotia located on the ancient microcontinent of Avalonia at the tropical equator. The Silurian is a superb geological period to be interested in – the marine fossils almost seem inspired by Dr. Suess – fantastic, beautiful and, at times, alien. Honeyman captured the aesthetic of Silurian life in his writing by marrying the romanticist movement of the early 19th century and the burgeoning ‘Age of Science’.

A Nova Scotia Museum diorama of the Silurian sea floor showing a trilobite, orthoceras nautiloid, brachiopod and gastropods. Photograph by Christian Laforce, NSM.

New Research of Historic Fossils

My preliminary encounter with the rocks at Arisaig was this summer. I received a Nova Scotia Museum Research Grant in conjunction with my Dalhousie BSc Honours thesis, which included a field component to examine carbonates and paleoclimate of the Silurian. While the section is well published on in modern literature, Honeyman’s archival collection has left a wealth of knowledge yet to be divulged. By combing through his fossils, publications and maps I was able to supplement and incorporate a historical perspective into modern research questions. My field work at the fossil site has been included under the Heritage Research Permit of the Curator of Geology, Tim Fedak, a co-supervisor of my thesis. Fossils are protected in Nova Scotia and a Research Permit is required to collect samples.

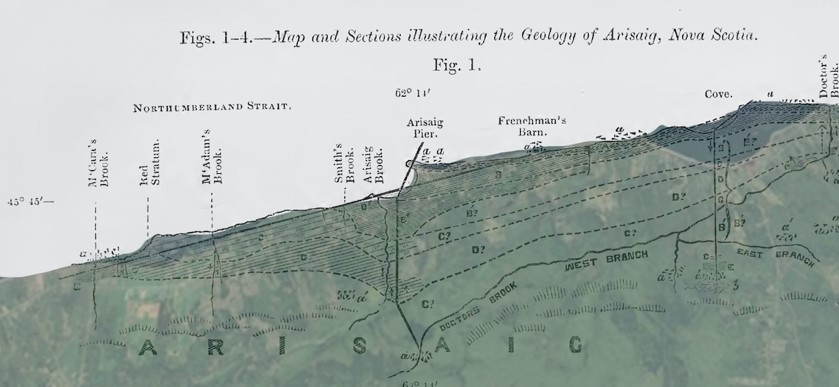

Above: Map of Arisaig (Honeyman,1864) overlaying Google Earth Satellite view of Arisaig coastline (2018).

Visiting the Silurian Outcrop

The best access to the Silurian rocks are via the Arisaig Provincial Park. Clambering down a small woodland path I arrive at the mouth of Arisaig Brook. Scanning the horizon from here one might miss the layers of past life taking refuge in the dark rock along the shore. The beachside cliffs extend west as arches and pinnacles; further on, nearly vertical limestone beds jut out from the beach sand. To the east, Arisaig pier sits bounded by ‘traps’ of Devonian aged basaltic flows (Melchin and MacRae, 2005).

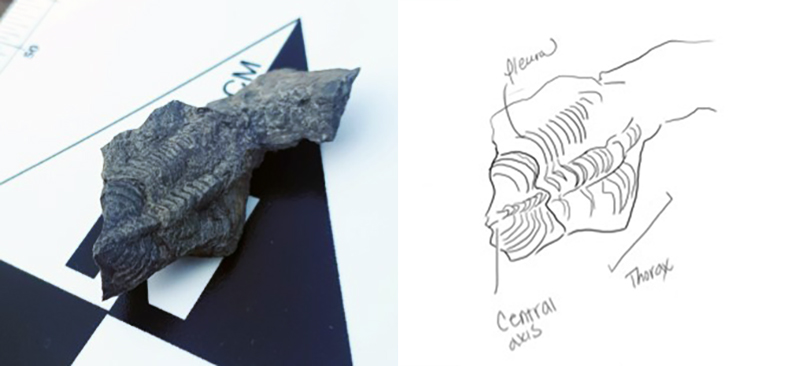

The rocks in Arisaig Brook are soft, especially the ones soaked from the stream, and dislodge like fresh ceramic tiles before a kiln firing. They are undoubtably shale, a slightly metamorphosed version of mudstone, and represent a deeper marine setting of deposition. I patiently till through the entrails of shale in the Arisaig Brook – when suddenly an unusual figure catches my eye. Small and complex, perfectly impressed into the rock, a trilobite fossil unlatches from the dark slab.

About the trilobites of Arisaig, David Honeyman had this to say in 1859:

“We have, after a five years’ search, met with only one whole specimen, and our consequent joy on its discovery was not less than that of Archimedes, on the occasion of his well-known exclamation, “ Eureka, eureka !” “

A New Discovery

I call out to my field supervisor “Wow! A trilo!” with similar enthusiasm to Honeyman 160 years ago.

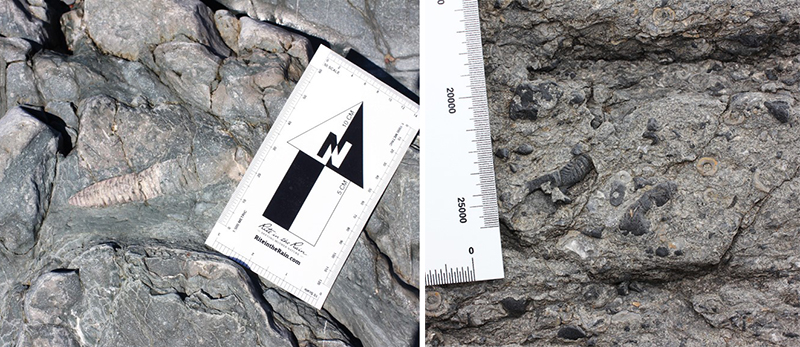

As I narrow my focus onto the flaky shale beneath my feet I can start to make out all kinds of evidence for this ‘life’ that once inhabited these ancient waters. As my focus adjusts I become surrounded by ancient sea lily Stems, shells of gastropods, trilobites, and Nautiloids spiralled and conical in form.

Above: A new Trilobite specimen found at Arisaig Brook – and interpretive line drawing to emphasize features.

Above: Left: Nautiloid entombed in limestone (Stonehouse Formation). Right: Trilobite and crinoids (Doctors Brook Formation).

Historical Significance

For Honeyman, the ‘graveyard’ of fossiliferous rocks were exemplary of nature’s grace. In comparing the process of fossilization to that of mummifying he says:

“We see nature, by chemical constituents of these rocks, oftentimes embalming their entombed inhabitants as no Egyptian physician could embalm ; not to present, after a few thousand years, a dry and withered mummy, but, after years whose numbers we cannot imagine, to present them almost, if not altogether, as lovely as when they were at first entombed.”

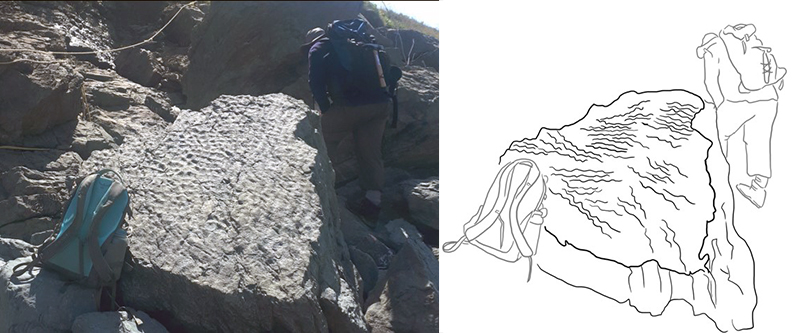

Towards the end of our field day, weighed down by backpacks full of rocks, my supervisor (Dr. Richard Cox) and I make our final advance down the shore towards McAras Brook. I glint up through my sunglasses to see a large slab of grey rock in my path. The texture of the rock face as immediately recognizable ripple bedforms. It occurs to me that the ancient ocean floor of the Silurian is now in my line of sight. I think back to Honeyman’s poetic account of exactly that:

"Our imagination takes its flight ; in ages long gone we exist;

in old ocean’s still abyss, at a depth of seventy fathoms, we take our stand.

We survey below, above, and around us ; there is life, activity and beauty."

Above: Wave-generated sinuous ripple marks – evidence of the shallow marine floor during the Silurian Period.

References

- Honeyman, D. (1859). Abstract of a Paper on the Fossiliferous Rocks of Arisaig. Transactions of the Nova Scotia Literary and Scientific Society,19-29.

- Honeyman, D. (1864). On the Geology of Arisaig, Nova Scotia. Proceedings of the Geological Society, 333-345.

- Honeyman, D. (1887). Giants and Pigmies (Geological) Earths Order of Formation and Life and Harmony of the Two Records. Halifax, N.S.: Museum and Booksellers.

- Melchin, M. J., & MacRae, R. A. (2005). The stratigraphy and paleontology of the Ordovician-Silurian Arisaig Group, Nova Scotia. Halifax, N.S.: North American Paleontological Convention.

Alexandra Bonham is an Earth Sciences Honours student at Dalhousie University, supervised by Dr. Richard Cox and Dr. Tim Fedak. Alexandra received a Nova Scotia Museum Research Grant in 2019 to study the historical collections at the Nova Scotia Museum, and her honours research focuses on study of ancient climates and ecosystems during the Silurian by analyzing stable isotopes preserved in the fossil shells of brachiopods at Arisaig.