Mosses for minimalist green roofs

By Dr. Sean R. Haughian, Curator of Botany

In the bustling concrete jungles of our cities, green spaces are like precious oases, offering a breath of fresh air amid the urban sprawl. But did you know that there's a humble yet mighty hero often overlooked in these green endeavors? Mosses – those tiny, often unnoticed plants – hold incredible potential for transforming our cities into greener, more sustainable environments.

Mosses are like the tiny superheroes of the plant world, capable of surviving extreme conditions like deep shade. They don’t even need soil to grow – they get all the nutrients and water they need from the atmosphere. They're like the ultimate survivors of the plant kingdom, thriving where others struggle. And the best part? They bring a host of benefits with them. From soaking up excess rainwater to providing homes for urban critters, mosses are tiny powerhouses of resilience, quietly working to make our cities healthier and more vibrant.

Traditional green roofs, where trays of soil are planted with a mix of succulent herbaceous plants, do a lot of great things for us. They improve building insulation, making cooling and heating more efficient. They reduce the urban heat-island effect, keeping cities cooler in the summer. They sequester carbon. They moderate stormwater runoff during heavy rainfall events, helping our urban drainage systems to cope by reducing peak flows and retaining water through dry periods. They also support biodiversity, providing habitat and food for many insects and birds.

But traditional green roofs also have some limitations. Older buildings, for instance, might not be able to support the weight of soil, plants, and drainage layers that are required by traditional green roofs. That's where the mighty mosses present us with an opportunity: with their lightweight nature and minimal maintenance needs, mosses could overcome many of these drawbacks, adding a touch of nature to our urban landscapes without breaking the bank, or your roof!

Recently, Professor Jeremy Lundholm (Saint Mary’s University) and sought to test whether we could simply inoculate asphalt-shingled roofs with a few common moss types to create a minimalist green roof. We thought the idea should work, because in many cases, mosses end up growing on our roofs anyways, so if we could expedite the process it might extend green roof opportunities to residential as well as light-weight commercial buildings, making green infrastructure more accessible to the general public.

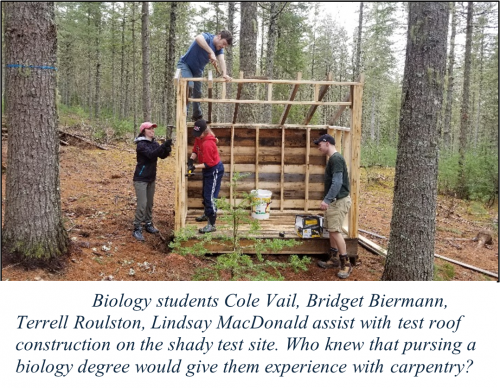

With a bit of help from the students in Jeremy’s research lab, we built two woodsheds to serve as test roofs on the Rural Innovation Campus of Community Forests International, near Sussex, New Brunswick.

We tested 3 main features to understand the best way to start a moss roof: rooftop exposure, moss type, and moss source. Rooftop exposure conditions included a sunny, south-facing roof, and a shady, north-facing roof. Moss types included Schreber’s feathermoss, a cap moss mixture, a lawn moss mixture, and a fork moss mixture. Moss sources included mosses harvested directly from the test site, and mosses that were grown in a laboratory first.

After 3 years of growth, it was clear that the exposed roof surface was not conducive to moss growth – everything had either blown off or shrivelled up and turned brown. The shady, sheltered site on the other hand had about half of the mosses survive and maintain a visible amount of cover, although none had expanded to become the luxurious carpet we’d hoped for. Some of the growth may have been hampered by excessive coverings of pine needles during the first two years. The species that did the best in the sheltered site were also those that are normally found in sheltered habitats – the Schreber’s feathermoss and the fork mosses. Finally, mosses had better survival when they were transplanted directly from the test site, rather than grown in the laboratory first – lab-grown mosses seemed to suffer from a lot of transplant shock in the first few months.

So are minimalist green roofs feasible? Sure they are. But just as you need to find the right spot in your garden for a sun-loving or shade-tolerant plant, you need to match the right type of moss to the right spot on a roof. Pay special attention to how shady or windy the places are, and try to match them to similarly shady or windy places on your roof. It’s also really important to ensure a firm attachment. Researchers in other places have used interlocking tiles, roll-out mats that can be clipped to roof edges and pinned in place, and even sometimes adhesives like superglue. You probably need at least a thin layer of something under the mosses, like burlap, to improve adhesion, and may want to consider laying burlap or some sort of mesh overtop of the mosses when they’re first installed, to prevent them from blowing off. Finally, don’t bother with starting them inside or in another location – just direct sow from your source area.

What's next for mossy roof research? We’d like to test some other types of mosses to see if others are particularly hardy to rooftop environments. With over 450 species to choose from in the Maritimes, we have a long way to go before we have a strong sense of which ones are best. It's an exciting time for moss enthusiasts and city dwellers alike, as we embark on what we hope is the beginning of a mini-green revolution.

Further reading:

Haughian, Sean R., and Jeremy L. Lundholm. Mosses for minimalist green roofs: A preliminary study of the effects of rooftop exposure, species selection, and lab-grown vs. wild-harvested propagule sources. Nature-Based Solutions 5 (2024) 100119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2024.100119.