Thoughts about Dartmouth Cove during SailGP

By Roger Marsters, Curator of History

The recent SailGP races in Halifax Harbour offered new ways to see a familiar place. In addition to folks crowding chilly wharves and hillsides in person, many more followed the races online. More than a few, including me, watched local webcams for backstage action at SailGP’s Dartmouth Cove marshalling yard.

As a historian I was struck by the image of boats being craned into the water at Collins Point, a place that was historically used as a place of execution. Looking closer, it was keen to see that alongside recent development here, contours of another, more ancient landscape persist. Look at the lower left side of this screen grab, where patches of gravel and sand reclaim the edges of the engineered shoreline.

For more than 250 years Dartmouth Cove has been altered to serve industrial purposes. From sawmills built on Mi’kmaw territory in the 1750s, to the railway in the 1880s and the COVE development more recently, industry has reshaped and hardened the cove’s shoreline.

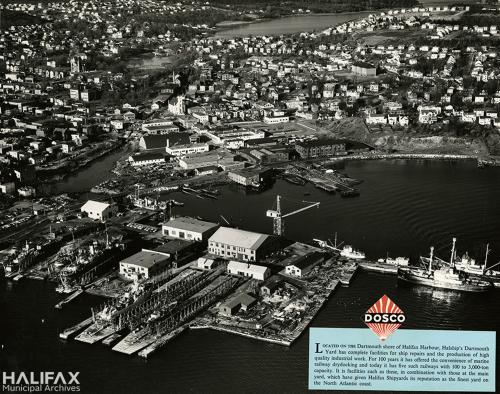

This post-Second World War aerial view shows Collins Point buried under the Marine Slips shipyard; the mouth of the Sawmill River (just behind the yard at left) clogged with foundry slag and blocked by a railway bridge; the shoreline defined by industrial piers and infill, and pocked with derelict vessels.

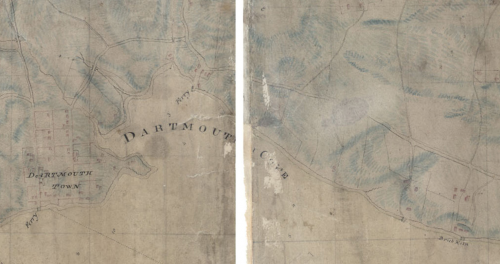

Nova Scotia Archives, Nova Scotia Archives Royal Engineers Maps and Plans Y.26 (detail)

This industrial landscape has been built over persistent natural features that, though (usually) out of sight, continue to shape life here. Dartmouth Cove was shaped by recent glaciation and sea-level rise. Its relatively shallow, brackish waters and marine resources supported L’nuk who sprouted from this place for thousands of years. People have adapted this landscape to better suit their needs for a very long time.

In this 1808 topographical map, made on the eve of intensive industrialization, several streams run into the cove between Collins Point and Woodside (marked here by the words “Brick Kiln”; below the site of the present NSCC campus). First, an outlet of the Dartmouth Lakes that settlers called Sawmill River; another running through a (now-vanished) marsh (the “musquash”) at the end of present Maitland Street; a stream running down from Maynard’s Lake near Old Ferry Road; and a spring at Sandy Cove, below NSCC.

HRM Collection, 1994.055.039.

All these spots remained sites for living and playing throughout this industrial transformation. Mi’kmaw people long continued to camp seasonally at preferred spots on the cove. I recall netting gaspereaux/alewives here during the 1970s, where the Sawmill River ran under the streets in a big, galvanized-steel culvert.

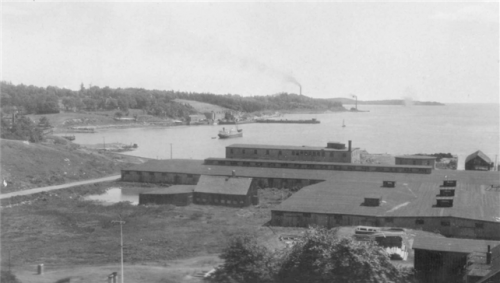

This view across the cove to the Collins Point peninsula c.1890 shows the longtime coexistence of industry and leisure here. Foregrounded against the densely developed, reclaimed land of the Marine Slips, local children play in a landscape that is industrial but publicly accessible. Note the gristmill directly behind the ship (the cove’s original industrial building), and the “soft” shoreline in the foreground.

HRM Collection, 1993.015.607

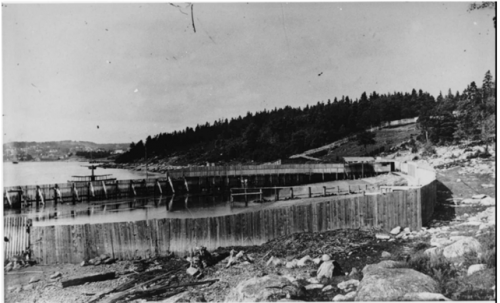

As lands adjacent to Dartmouth Cove were radically altered by industrial development, natural features continued to assert themselves. This view of the Dominion Molasses premises at Maitland Street—formerly the “musquash”, a long-time skating spot for Dartmouthians—shows how this former wetland long endured, despite development.

This south-facing view looks across to the Department of Transport base (the present COVE site) and to Sandy Cove, Mount Hope, and the Woodside sugar refinery beyond. During the 1950s the wooded ridge at left (sometimes called Prince Arthur Hill) was completely transformed by suburban housing development.

HRM Collection, 1994.009.095

From the mid-1800s onward, settlers’ leisure and industrial activities came into conflict Mi’kmaw peoples’ long-time use of this landscape. This view of Sandy Cove, looking north towards Dartmouth, shows a preferred spot where Mi’kmaw families lived and worked seasonally; in later years making baskets and other commodities for sale across the harbour in Halifax.

By the 1850s young Haligonians were rowing across the harbour in the opposite direction on hot days to swim at Sandy Cove beach. By the 1870s, Halifax entrepreneurs enclosed and expanded the beach, privatizing the shore and ending centuries of customary occupation and use. Mi’kmaw people persisted in visiting other sites on the cove and maintain their ancestral presence here.

Roger Marsters photo

In 1884/1885 the Dartmouth shore from the Harbour Narrows to Woodside was hardened with embankments and trestles to carry a spur-line of the Intercolonial (later Canadian National) Railway. Access was further limited in the 1950s, as children from new suburban developments up the hill endangered themselves among the cove’s rail cars and derelict ships.

By the 1970s much of Dartmouth Cove was publicly inaccessible and, it seemed, irretrievably altered by centuries of commercial and industrial development. In recent years this has changed. New development and active-transportation corridors have re-established access in ways that revives coexistence of leisure and occupational uses.

Restored access allows people today to experience Dartmouth Cove in new ways. SailGP is a dramatic example. But there are less dramatic discoveries here, too: persistent marine life; the remains of long-vanished industries; and, historic landscape features—such Sandy Cove beach, above—still there when the tide drops low enough.