Whale Bones in the Museum Backyard

Brenna Frasier, Curator of Zoology, Nova Scotia Museum

If you peek into the backyard of the Museum of Natural History, you will see a large skeleton on view. These bones belong to the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis), a critically endangered species with less than 400 individuals remaining in the North Atlantic. This species is one of three species in the genus Eubalaena, the others being the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) and the Southern right whale (Eubalaena australis).

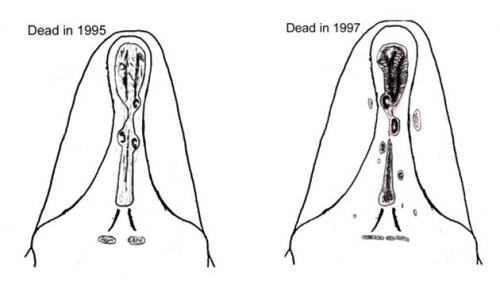

The skeleton is a composite of bones from two animals: NEA #2250, a subadult male that died in 1995, and NEA #2450, a subadult female that died in 1997. Both individuals were found dead in Nova Scotia’s waters and at that time curators with the Nova Scotia Museum acquired parts of each animal. It is believed that both individuals died because of a vessel collision.

The skeleton you see on display is incomplete – some of the bones have been kept in the permanent collection of the Nova Scotia Museum, so that they are available to study in the future, others were simply not collected.

A bit about right whales

North Atlantic right whale once had a distribution extending across the North Atlantic Ocean. Today, following centuries of population reductions due to whaling, the species is found primarily in the western North Atlantic ranging between the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the coast of Florida. They frequent the waters around Nova Scotia but are rarely seen because they tend to be far offshore.

Right whales are a large baleen whale that can grow to be upwards of ~15 meters and ~70,000 kg! They have a large head (up to 1/3 of their body length!) encompassing a strongly arched jaw that holds 400 – 600 plates of baleen, each up to 2-3 m in length. Right whales are also distinctive in that they have large paddle-shaped flippers and a ‘V’-shaped blow when they come to the surface of the water to breathe.

Another unique feature of this species is that their heads and chins have areas of thick cornified skin known as callosities. During their first year of life, this area of skin becomes covered in cyamids, or whale-lice, which make the area appear white. These patches of rough skin remain the same shape throughout their lives and are used by researchers as distinguishing features to identify individuals.

Two species of cyamid, a small crustacean, collected from the callosity of a North Atlantic right whale (NSM78418.002). The larger, more rounded specimen on the left is Cyamus ovalis, while the smaller specimen on the right is Cyamus gracilis. A third species, Cyamus erraticus, commonly inhabits genital and mammary slits, as well as wounds.

For over 40 years researchers from the United States and Canada have been monitoring this species in our waters. During this time, almost 800 individuals have been identified. You can explore the population by looking through the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog. You can even find images and the sightings histories of NEA #2450 and #2250.

Historically, the right whale was considered the ‘right’ whale to hunt, because it is large, has a thick blubber layer (~12cm), has long plates of baleen, moves relatively slowly relative to the faster rorqual whales such as the fin and blue whales, and it floats when it is dead. The species was commercially hunted starting in at least the 11th century for its baleen and blubber. While blubber was rendered down to be used as a lubricant, and as fuel and wax for lighting. Baleen, with its plastic-like flexibility, had a wide variety of uses in products such as umbrellas, corsets, hoop skirts, and whips.

No longer hunted, but still dying.

The North Atlantic right whale is no longer hunted and has been internationally protected since 1935. However, they are still dying in our waters due to entanglements with fishing gear and vessel collisions. The deaths of both individuals whose bones we have on display were due to probable vessel collisions. NEA #2250 was found with a ~5m opening along his back exposing several crushed vertebral discs. NEA #2450 had a broken jaw and evidence of blunt force trauma along her left flank.

In the table below, you will see information on NEA #2250 and NEA #2450.

|

|

Individual 1 |

Individual 2 |

|

Individual |

NEA #2250 |

NEA #2450 |

|

Age |

Subadult, at least 4 years |

Subadult, at least 4 years |

|

Sex |

Male |

Female |

|

Length |

12.7 m |

12.5 m |

|

Mother |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Father |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

First seen alive |

September 21, 1992, Bay of Fundy |

August 17, 1994, Bay of Fundy |

|

First seen dead |

October 19, 1995 |

August 19, 1997 |

|

Necropsy date |

Not conducted |

August 20-21, 1997, Flour Cove, Long Island, NS |

|

Location on shore |

Long Island, Digby County, Nova Scotia |

Flour Cove, Long Island, Digby County, Nova Scotia |

|

Cause of death |

Probable vessel collision |

Vessel collision |

We think that having the bones on display here in the backyard is impactful, enabling us to show the sheer size of the animal but also to have an opportunity to highlight the ongoing struggle that this endangered species must undergo in a challenging marine environment. Right whales face a variety of challenges – not just the threat of entanglement in fishing gear and vessel collisions. Increasing ocean noise and changing food distribution and availability cause them to shift their habitat use patterns, making monitoring and protection very difficult. Internationally, government agencies are working towards inclusive and adaptive regulation and management strategies that work for the whales but also for fishing and shipping industries.

Where can I find more information on North Atlantic right whales?

Websites:

North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog (New England Aquarium)- http://rwcatalog.neaq.org/Default.aspx

The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium (https://www.narwc.org/)

The New England Aquarium – North Atlantic right whale (https://www.neaq.org/animal/right-whales/)

Canada Species At Risk Public Registry – (North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis) - Species search - Species at risk registry (canada.ca))

Books:

Kraus, Scott D., and Rosalind M. Rolland, eds. The urban whale: North Atlantic right whales at the crossroads. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Kraus, Scott, and Kenneth Mallory. Disappearing Giants: The North Atlantic Right Whale. Bunker Hill Publishing, Inc., 2003.

Tobin, Deborah. Tangled in the Bay: The story of a baby right whale. Nimbus Publishing, 2003.