Emancipation Day Exhibit

Items from the Nova Scotia Museum Collection

2021 marks the first year the Province of Nova Scotia officially recognizes Emancipation Day. Emancipation Day is marked throughout the Commonwealth as the anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834.

The Nova Scotia Museum is using this first recognition of Emancipation Day in the province to highlight items from the Collection. These items provide evidence and insight into the lives of people of African descent who have lived in or been connected with Nova Scotia. These important pieces of history will be on temporary exhibit at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic and the Museum of Natural History during August 2021. To further increase access to these important items, they are also shared here online for those unable to see them at the museums in Halifax.

Nova Scotia’s connection to the West Indies, enslavement, abolition, and the role of African Nova Scotians throughout history have largely been overlooked. These temporary exhibits are only a first step in incorporating these narratives into museum exhibits and collection. It is our hope that the renewal of our exhibits will allow more Nova Scotians to feel that they are reflected in the museum’s content and remain relevant going forward.

Archaeology and the Early Black History of Nova Scotia

Historical or archival records about enslaved people, servants, or laborers are hard to find. Researchers use archaeology to reveal physical evidence of these stories. One such story explored by archaeologists at the Nova Scotia Museum is the Ruggles’s family settlement of North Mountain in Annapolis County. This Loyalist family had enslaved individuals, servants, and laborers who worked to establish a new homestead for the Ruggles family after they left Massachusetts following the American Revolution. Four artifacts from this archaeological fieldwork show evidence of their daily lives.

Whetstone or Sharpening Stone

This whetstone was excavated in an eighteenth-century cellar which sits below a modern house. This whetstone was used often and likely by folks working in the cellar area of the house who needed sharp tools for daily tasks. Notice the groove lines left from moving a blade across the stone.

Brick Fragment

Clay brick fragments are one of the most common artifacts found on archaeology sites of the colonial period. At this site, interpreted as a laborer’s hut, there was very little brick. Look at the rough surface of this brick, it appears to be handmade. The structural elements of the hut, like the rudimentary foundation and the hearth, were constructed of local stone layered without mortar. If not for building, how was this brick used?

Iron Knife

While excavating at a laborer’s hut, the remains of a knife were found. Over time, metal and organic objects decay in the acidic soils of Nova Scotia. The tang, the narrow stem end, would have had a bone or wooden handled riveted around it. Only part of the blade is left.

Building Hardware?

Archaeologists often find artifacts that are challenging to identify. This iron artifact may be a fragment of building or window hardware or perhaps some kind of tool. It was found about 20 cm below the surface, next to a stone wall and not far from a hearth area. Is it architectural or part of a tool used in the fireplace?

Cultural History

There are few objects from the Nova Scotia Museum Cultural History collection that represent Nova Scotia’s Black communities. This is an area of development for the Collection. The rare surviving objects however are powerful. Embedded within them all are the stories of individuals who fought to establish, retain, and further the rights and freedoms of a true emancipation.

Margru’s Cloth

The maker of this cloth was named Margru, and she was just eight years old when she was enslaved and experienced the revolt aboard the slave ship La Amistad in 1839. The dramatic trial in Connecticut that followed led to her freedom two and a half years later. The cloth is of traditional West African design and given as a gift to Eliza Ruggles Raymond, a Nova Scotian missionary, in the early 1840s in Sierra Leone.

NSM Cultural History, 2004.7.206

African Nova Scotian basketry

Made for sale at Halifax’s city market, these splint-wood baskets were woven by three generations of African Nova Scotian women, descendants of Black Refugees. Woven in slavery and then after emancipation as a means of living, for over 100 years this craft tradition passed from mother to daughter to become a symbol of artistry, resilience, and community.

NSM 34.191d by Irene Selena Sparks Drummond (Cherry Brook)

NSM 87.103.1 by Edith Drummond Clayton (Cherry Brook)

NSM 83.70.3 by Rosalind Drummond (Lucasville).

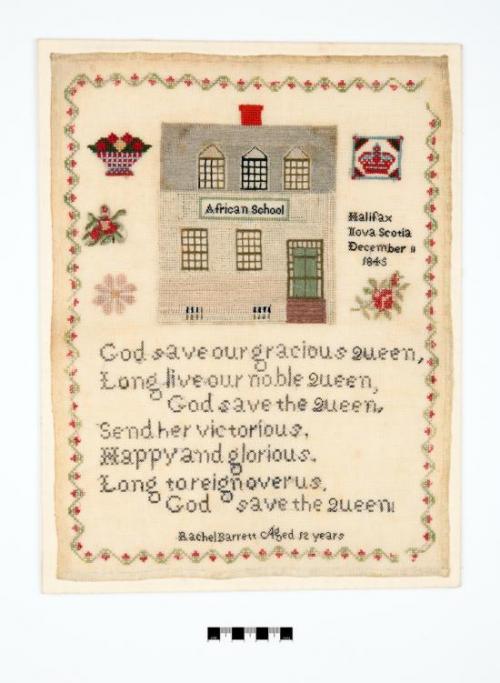

In 1845, Rachel Barrett, most likely the child of a Black Refugee, stitched by hand an embroidery known as a sampler as part of her education at Halifax’s African School. Barrett’s sampler is the first of its kind discovered in Nova Scotia. It was stitched when schools for Black Nova Scotians were racially segregated, and subject matter was gendered. Despite this, parades celebrating emancipation began at the African School’s doorsteps, demonstrating its importance to the community.

NSM 2018.14.1

African Abolition Society founder - Reverend Richard Preston

This pen and ink sketch depicts the Reverend Richard Preston, a former slave from Virginia and War of 1812 Refugee, on horseback. Preston was a renowned orator, Baptist minister, educator and co-founder of Halifax’s African Abolition Society.

NSM P149.29, by Dr. J.B. Gilpin.

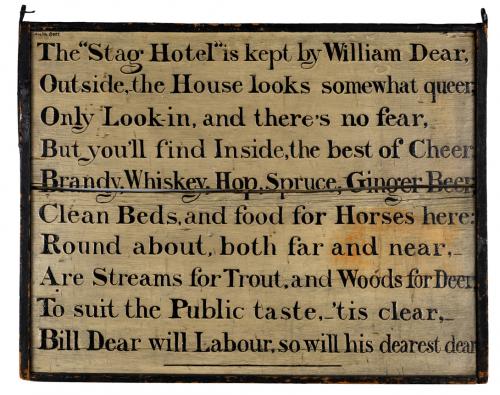

The Stag Hotel sign (c.1835) – proprietors the Dear family

This cleverly worded advertising sign hung outside the Stag Inn, Preston, established by former Maryland slaves and War of 1812 Black Refugees, the Dear family. William Dear (or Dare) escaped enslavement by Dr. John Dare but refused to leave the county until he had rescued his wife Nancy and her brother. Having found emancipation in Nova Scotia, anti-Black racism and injustice did not end, but their hard work resulted in a business they could call their own.

NSM 36.70

Abolitionist Medallion

The image of a kneeling African person in chains became a powerful symbol for the abolition movement. Beginning in 1787, abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic wore or displayed items such as these to show their support for the movement. At a time when women could not vote or join political groups, these objects enabled them to publicly challenge racial attitudes. However, not everyone who displayed these images felt solidarity with the enslaved or understood the horrors of the slave trade. Some were associating themselves solely with the politically charged abolition movement.

NSM Cultural History, 2015.13.4-6.